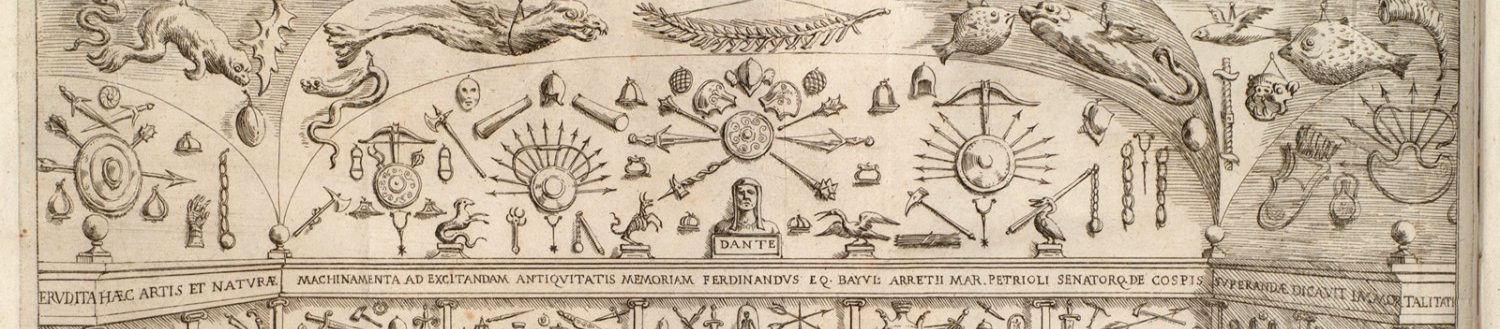

I didn’t know well how to begin this post, and I also wanted to give these bots a try, so I’ve got the picture above from LensGo and I’ve asked chatGPT to generate a short story about Dr. Spock gambling against Maxwell’s Demon. Here it is:

Dr. Spock, the renowned physicist, found himself in an unexpected predicament. Across the green-felted table in a high-stakes casino, he faced an unlikely opponent: Maxwell’s Demon, a quantum-imbued entity known for challenging the laws of thermodynamics.

Their game wasn’t the usual casino fare. Instead, they wagered on the concept of dissipated work and energy. Dr. Spock, guided by the principles of scientific rationality, made precise calculations. Maxwell’s Demon, with a mischievous glint in its eye, played the odds.

As the final bets were placed, the cards were revealed, and the roulette wheel spun. In the end, it was Dr. Spock’s logical deductions that won the day, while Maxwell’s Demon learned that even in its magical universe, the laws of thermodynamics held sway. With a nod of acknowledgment, the demon vanished into the enigmatic folds of uncertainty, leaving Dr. Spock to ponder the intersection of science and chance.

Meh. Not super impressive… And why Maxwell’s Demon should be “quantum-imbued”? I didn’t prompt for anything quantum…

Anyway, this was to introduce a paper that we recently published in Physical Review Letters (paper freely available on the arXiv), discussing the second law of thermodynamics and Crooks’ fluctuation relations from the point of view of expected utility theory (EUT), which is what economists use to model betting strategies and rational agents.

The punchline is that all Rényi divergences between forward and backward process have the exact operational interpretation of how much a rational betting agent, with risk aversion r=𝛼-1, would be willing to pay to avoid betting on the performance of a stochastic thermal engine. In EUT jargon, this is called the certainty equivalent value. Thus, for example, the conventional relative entropy (𝛼=1) is not only the usual average dissipated work, but also the certainty equivalent amount for a perfectly rational agent (like the Spock in the picture…) who is neither risk-seeking nor risk-averse (r=0). Instead, for an infinitely risk-averse player (𝛼=r=∞), who cannot tolerate any uncertainty and simply wants to walk away from any possible gamble, the certainty equivalent amount naturally corresponds to the worst-case scenario of maximum dissipated work, as measured by Dmax, thus recovering a result of Yunger-Halpern et al. We are also able to describe the zoology of extremely risk-seeking, happy-go-lucky gamblers with r<-1 (𝛼<0), although the corresponding certainty equivalent amount is no longer a properly defined Rényi divergence.

We had fun with this paper: putting Maxwell’s Demon and economics together makes for a lot of jokes… Speaking of which, here is one by the bot:

Why did Maxwell’s Demon decide to walk into Wall Street?

Because he heard there was a hot market for sorting bull and bear markets!

OK, bot, nice try…